#P13470. [GCJ 2008 #3] How Big Are the Pockets?

[GCJ 2008 #3] How Big Are the Pockets?

题目描述

Professor Polygonovich, an honest citizen of Flatland, likes to take random walks along integer points in the plane. He starts from the origin in the morning, facing north. There are three types of actions he makes:

- 'F': move forward one unit of length.

- 'L': turn left 90 degrees.

- 'R': turn right 90 degrees.

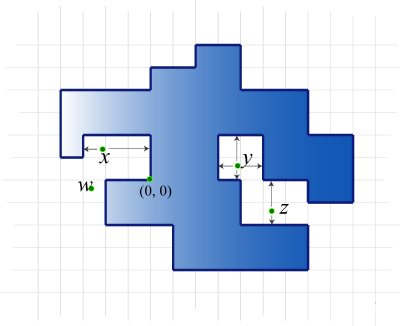

At the end of the day (yes, it is a long walk!), he returns to the origin. He never visits the same point twice except for the origin, so his path encloses a polygon. In the following picture the interior of the polygon is colored blue (ignore the points , , , and for now; they will be explained soon):

Notice that as long as Professor Polygonovich makes more than turns, the polygon is not convex. So there are pockets in it.

Warning! To make your task more difficult, our definition of pockets might be different from what you may have heard before.

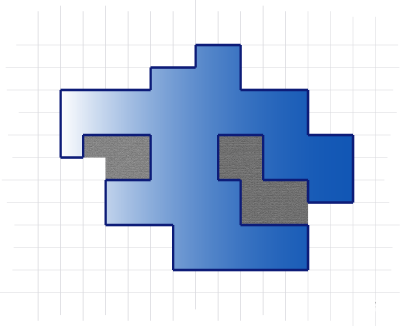

The gray area below indicates pockets of the polygon.

Formally, a point is said to be in a pocket if it is not inside the polygon, and at least one of the following two conditions holds.

- There are boundary points directly both east and west of ; or

- There are boundary points directly both north and south of .

Boundary points are the points traversed by Mr. Poligonovich on his walk (these include all points, not just those with integer coordinates).

Consider again the first picture from above. Point satisfies the first condition; satisfies both; satisfies the second one. All three points are in pockets. The point is not in a pocket.

Given Polygonovich's walk, your job is to find the total area of the pockets.

输入格式

The first line of input gives the number of cases, . test cases follow.

Each test case has the description of one walk of Professor Polygonovich. It starts with an integer . Following are "S T" pairs, where is a string consisting of 'L', 'R', and 'F' characters, and is an integer indicating how many times is repeated.

In other words, the input for one test case looks like this: ...

The actions taken are the concatenation of copies of , followed by copies of , and so on.

The "S T" pairs for a single test case may not all be on the same line, but the strings will not be split across multiple lines. The second example below demonstrates this.

输出格式

For each test case, output one line containing "Case #: ", where is the 1-based case number, and is the total area of all pockets.

2

1

FFFR 4

9

F 6 R 1 F 4 RFF 2 LFF 1

LFFFR 1 F 2 R 1 F 5

Case #1: 0

Case #2: 4

提示

Sample Explanation

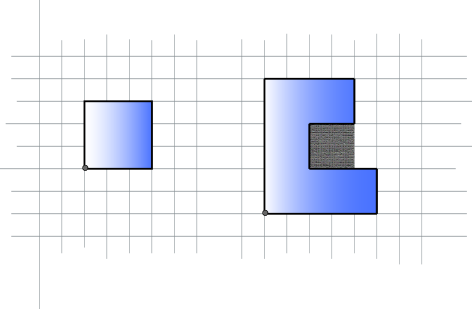

The following picture illustrates the two sample test cases.

Limits

- (bounded from above by constraints in the problem statement, "Small dataset" and "Large dataset" sections)

- The path, when concatenated from the input strings, will not have two consecutive direction changes (that is, there will be no 'LL', 'RR', 'LR', nor 'RL' in the concatenated path). There will be at least one 'F' in the path.

- The path described will not intersect itself, except at the end, and it will end back at the origin.

Small dataset (5 Pts, Test set 1 - Visible)

- The length of each string will be between 1 and 16, inclusive.

- The professor will not visit any point with a coordinate bigger than 100 in absolute value.

Large dataset (10 Pts, Test set 2 - Hidden)

- The length of each string will be between 1 and 32, inclusive.

- The professor will not visit any point with a coordinate bigger than 3000 in absolute value.